Spider

Spiders are invertebrate animal(s) that produce silk, have eight legs and no wings. More precisely, a spider is any member of the arachnid order Araneae, an order divided into two sub-orders: the Opisthothelae (which include the infraorders Mygalomorphae (trapdoor and tarantula spiders) and Araneomorphae (the modern spiders)) and the Mesothelae, which contains the Family Liphistiidae, burrowing spiders from Asia. more...

The study of spiders is known as arachnology.

Many spiders hunt by building webs to trap insects. These webs are made of spider silk, a thin, strong protein strand extruded by the spider from spinnerets most coomonly found on the end of the abdomen. All spiders produce silk, although not all use it to spin elaborate traps. Silk can be used to aid in climbing, forming smooth walls for burrows, building egg sacs, wrapping prey, temporarily holding sperm and for many other applications.

Morphology and development

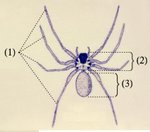

Spiders, unlike insects, have only two body segments instead of three; a fused head and thorax (called a cephalothorax or prosoma) and an abdomen (called the opisthosoma), supported by an exoskeleton composed mainly of chitin.

Spiders also have eight legs (insects have six), no antennae, and their eyes are single lenses rather than compound eyes. Additionally spiders have pedipalps (or just palps), at the base of which are coxae or maxillae next to their mouth that aid in maasticating food; the ends of the palp are modified in adult males into elaborate and often species specific structures used for mating.

Respiration and circulation

Spiders have an open circulatory system, meaning they don't have true blood or veins for it to travel in. Rather, their bodies are filled with haemolymph, which is pumped through arteries by a heart into spaces called sinuses surrounding their organs.

Spiders have developed several different respiratory anatomies, based either on book lungs, a tracheal system, or both. Primitive mygalomorph spiders generally have only a pair of book lungs filled with haemolymph, where openings on the ventral surface of the abdomen allows air to enter and diffuse oxygen. Modern araneomorph spiders often have a single book lung in addition to spiracles which deliver air into the tracheae, where oxygen is then diffused into the haemolymph. In the tracheal system oxygen interchange is much more efficient, enabling cursorial hunting (hunting involving rapid pursuit) and other advanced characteristics.

Vision

Spiders usually have eight eyes in various arrangements, a fact which is used to taxonomically classify different species. Sometimes one pair of eyes is better developed than the rest, or there are only six pairs, or no eyes at all. Several families of hunting spiders have developed good to excellent vision, such as wolf spiders and jumping spiders. However, most spiders that lurk on flowers, webs and other fixed locations waiting for prey have very poor eyesight, but possess extreme sensitivity to vibrations for hunting.

Defense

Some tarantula have a patch of urticating hairs on their abdomens for defense, which are generally absent on modern spiders and Mesothelae. Certain other species have specialized defense tactics. For example, the Golden Wheeling spider of the desert escapes Tarantula Wasps (a species of wasp that lays its eggs in a paralyzed spider so the larvae have enough food when they hatch) by flipping onto its side and cartwheeling away.

Life cycle

The spider life cycle progresses through three stages: the embryonic, the larval, and the nympho-imaginal (Foelix, 1996).

Between the time an egg is fertilized and the spider begins to take the shape of a spider is referred to as the embryonic stage (Foelix, 1996). As the spider begins to look more like a spider it enters the larval stage (Foelix, 1996). It enters the larval stage as a prelarva and, through subsequent molts, it reaches its larval form, a spider-looking, non self-sufficient animal feeding off its yolk supply (Foelix, 1996). After a few more molts, also called instars, body structures become differentiated; all organ systems are complete and the animal begins to hunt on its own; it has reached the nympho-imaginal stage (Foelix, 1996). This stage is differentiated by two sub-stages: the nymph, or juvenile stage and the imago, or adult stage (Foelix, 1996). A spider does not transition from the nymph to the imago until it has become sexually mature (Foelix, 1996). Once a spider has reached the imago stage, it will remain there until its death. Many spiders may live only about a year, but a number will live two years or more, overwintering in sheltered areas (the annual influx of 'outdoor' spiders into houses in the fall is due to this search for a nice warm place to spend the winter).

Reproduction

Spiders reproduce by eggs laid in silk bundles called egg sacs.

Spiders often use elaborate mating rituals (especially in the visually advanced jumping spiders) to allow the male to approach close enough to inseminate the female without triggering a predatory response. Assuming that the approach signals are exchanged correctly, the male spider must make a timely departure after mating to escape before the female's normal predatory instincts come back into operation.

Sperm transmission is an indirect process. When a male is ready to mate, he will spin a web pad onto which the sperm is discharged. He then dips his palps (also known as 'palpi'), the small, leg-like appendages on the front of his cephalothorax, into the sperm, picking it up by capillary attraction. Mature male spiders have swollen bulbs on the end of their palps for this purpose, and this is a useful way to identify the sex of a spider in the field. With his palps thus 'charged' he then goes off in search of a female. The act of copulation occurs when the male inserts one or both palps into the female's genital opening, known as the epigyne. He transfers his sperm into the female by expanding the sinuses in his palp.

Very unusual behaviour is seen in spiders of the genus Tidarren, as the male amputates one of his palps before maturation and enters his adult life with one palp only. The palpi constitute 20% of its body mass, and since this weight greatly impedes its movement, the spider detaches one of the two to gain mobility. In the Yemeni species Tidarren argo, the remaining palp is then torn off by the female. The separated palp remains attached to the female's epigynum for about four hours and apparently continues to function independently. In the meantime the female feeds on the palpless male. (Journal of Zoology (2001), 254:449-459 Cambridge University Press DOI:10.1017/S0952836901000954 )

Read more at Wikipedia.org